麻醉医师一直是患者安全的主要倡导者,长期以来深刻认识到麻醉工作区手卫生的重要性。1手污染与多个麻醉工作区宿主的病原体传播有关,将从医务人员手部培养的细菌和致感染病原体进行的基因组分析证实,医务人员会传播导致患者感染的病原体。2,3,4金黄色葡萄球菌 (S. aureus) 在麻醉工作区宿主之间的传播与手术部位感染 (Surgical Site Infection, SSI) 风险的增加有关。5事实上,当病原体对使用的预防性抗生素敏感时,SSI 风险会增加五倍以上,而当病原体对使用的预防性抗生素具有耐药性时,SSI 风险会增加九倍。6为降低这种风险,需要采取多种措施来预防 SSI。7将改善手卫生纳入其中,可显著减少金黄色葡萄球菌的传播和 SSI。8,9这些发现可推动所有术中人员手卫生依从性的改善,而麻醉医师将发挥带头作用。

麻醉医师一直是患者安全的主要倡导者,长期以来深刻认识到麻醉工作区手卫生的重要性。1手污染与多个麻醉工作区宿主的病原体传播有关,将从医务人员手部培养的细菌和致感染病原体进行的基因组分析证实,医务人员会传播导致患者感染的病原体。2,3,4金黄色葡萄球菌 (S. aureus) 在麻醉工作区宿主之间的传播与手术部位感染 (Surgical Site Infection, SSI) 风险的增加有关。5事实上,当病原体对使用的预防性抗生素敏感时,SSI 风险会增加五倍以上,而当病原体对使用的预防性抗生素具有耐药性时,SSI 风险会增加九倍。6为降低这种风险,需要采取多种措施来预防 SSI。7将改善手卫生纳入其中,可显著减少金黄色葡萄球菌的传播和 SSI。8,9这些发现可推动所有术中人员手卫生依从性的改善,而麻醉医师将发挥带头作用。

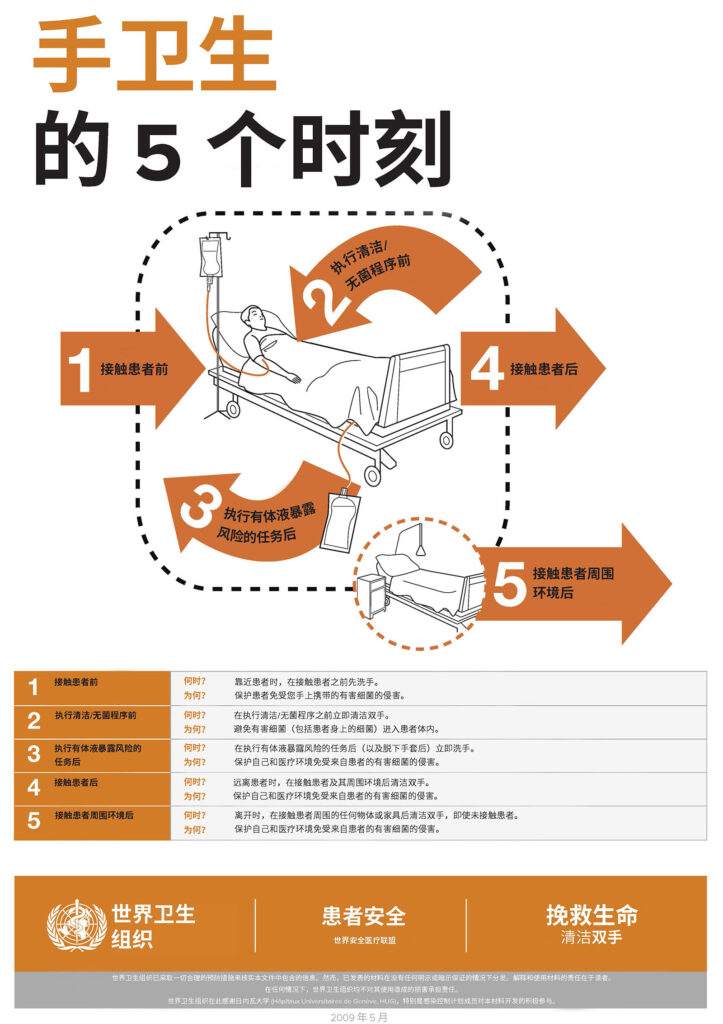

麻醉工作区环境复杂,包括患者、手术床/手术台、麻醉机、带输液装置的静脉输液 (IV) 架、装有清洁用品的推车以及药物(存放在推车或单独药物站内)。在常规麻醉操作中,麻醉医师与患者和麻醉工作区的多个组成部分进行互动。10,11鉴于这一环境的复杂性,有必要进行手部消毒,以中断传播事件并减少感染传播。世界卫生组织 (World Health Organization, WHO) 将在其之后应进行手卫生的事件定义为“手卫生的五个时刻”。12这些需要手卫生的时刻包括:接触患者前、清洁或无菌操作前、接触患者后、执行有体液暴露风险的任务后以及接触患者周围环境后(图 1)。12遵循 WHO 建议和类似建议将要求麻醉医师进行手卫生的频率达到每小时 54 次13至每小时 150 次。11,13然而,研究表明,麻醉医师的手卫生频率低于每小时 1 次。14显然还有很大的改进空间。考虑到细菌在环境中无处不在,阻断病原体的传播似乎不太可能实现。然而,研究表明,将医务人员手部的金黄色葡萄球菌水平降至低于 100 个菌落形成单位 (Colony-forming Units, CFU) 是一个可以实现的目标,这有助于保护患者。9,15

APSF 患者安全优先事项倡导小组建议麻醉医师在提供麻醉照护期间每小时至少进行约 8 次手卫生。16 以每小时 8 次的频率洗手或使用手部消毒液,可以有效地减少环境和旋塞污染以及后续感染。14然而,尚不清楚促进这一频率的手卫生合规性的适当方法。16未来的重要研究应关注产品(如含酒精的产品或肥皂和水)、洗手液位置、清洁技术和潜在风险。

虽然使用含酒精的溶液可对手部进行有效消毒,但应使用肥皂和水对明显污染的手部或在可能接触孢子形成生物的情况下进行消毒。14,17 由于洗手槽必须位于手术室之外,酒精成为麻醉医师的主要手卫生选择,而且由于酒精对皮肤的刺激性小于肥皂和水,因此可能会降低皮肤刺激的风险,进而减少刺激皮肤上的细菌数量。18,19

洗手液的位置应由任务密度(一段时间内需要完成的任务数量)决定。医疗照护感染预防组织建议将洗手液放置在患者照护区域内易于拿取的位置。20使用放置在麻醉工作区外的洗手液(例如,置于墙上或手术室入口附近)可能会扰乱患者照护。任务密度的重要性已得到清晰界定。在一项研究中,麻醉医师使用了个性化的体戴式酒精洗手液,将手卫生依从性提高了 37 倍,从而降低了环境和旋塞污染以及与医疗照护相关感染的发生率。14 其他研究人员评估了在多方面计划中将洗手液放置在医务人员左侧的静脉输液架上的操作。8,9 将洗手液放置在此位置可以降低细菌传播及后续 SSI 的发生率。8,9

由于医务人员的手部污染与环境污染有关,提高环境清洁的频率和质量也有助于加强手卫生改善工作。在一项研究中,将麻醉工作区分为“清洁”和“污染”区与达到 ≥ 100 CFU 的部位比例降低有关。14,21 显而易见,酒精洗手液应放置在清洁区。例如,可以使用安装架将洗手液固定在麻醉机或用品推车上,或固定在静脉输液架上。如果固定在静脉输液架上,则应小心保护患者、手术区域和下方的电插头免受液滴飞溅(表 1)。

表 1:麻醉工作区手部消毒液位置的潜在考虑因素。

虽然麻醉医师必须能够随时使用手部消毒液,但也有潜在危险需要考虑。所有含酒精的消毒液都含有 60%–80% 的乙醇或异丙醇和水。这是因为需要足够的水分来水解微生物膜并减缓产品的蒸发。22,23 由于酒精产品易燃,消防规范规定了手术室内允许存放的消毒液总量和酒精洗手液之间的最小间距。洗手液之间必须保持至少四英尺的距离,并且一个房间内洗手液的总体积不得超过 1.2 升。24 美国疾病控制和预防中心 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) 也支持这一消防安全建议。25 个性化、体戴式酒精洗手液和静脉输液架上的单手酒精泵的体积小于 3 盎司。8,9,14 虽然尚无与手部消毒液有关的火灾报告,但也应将此风险考虑在内。

综上所述,麻醉医师改善手卫生是减少细菌传播及感染的重要方法之一。应鼓励麻醉医师在常规麻醉照护期间每小时进行 8 次手卫生操作。在麻醉工作区内,含酒精的消毒液应放置在临床医生清晰可见、清洁且方便拿取的位置。

Jonathan E. Charnin, MD, FASA 是梅奥诊所(明尼苏达州罗切斯特)麻醉和围手术期医学科的麻醉学助理教授。

Brendan T. Wanta, MD 是梅奥诊所(明尼苏达州罗切斯特)麻醉和围手术期医学科的麻醉学助理教授。

Richard A. Beers, MD 是上州医科大学(纽约州锡拉丘兹)的名誉教授。

Jonathan M. Tan, MD, MPH, MBI, FASA 是洛杉矶儿童医院和南加州大学(加利福尼亚州洛杉矶)麻醉学和重症监护医学系的临床麻醉学和空间科学助理教授及分析和临床有效性副主席。

Michelle Beam, DO, MBA, FASA, FACHE 是宾夕法尼亚大学医学院(宾夕法尼亚州西切斯特)的麻醉医师。

Sara McMannus, RN, BSN, MBA 是脓毒症联盟的临床顾问。

Desiree Chappell, MSNA, CRNA 是 NorthStar Anesthesia(德克萨斯州欧文)的临床质量副总裁。

Randy W. Loftus, MD 是梅奥诊所(明尼苏达州罗切斯特)麻醉和围手术期医学科的麻醉学副教授。

Jonathan Tan 接受了麻醉患者安全基金会、麻醉教育与研究基金会 (Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research, FAER) 和南加州环境健康科学中心 (Southern California Environmental Health Sciences Center) 的研究资助。他是 GE Healthcare 和 Edwards LifeSciences 的顾问。

Desiree Chappell 是 Medtronic 和 Edwards Life Sciences 的发言人和 ProVation 的顾问委员会成员。

Randy Loftus 报告该研究的经费来自 NIH R01 AI155752-01A1“BASIC 试验:改进循证方法和监测的实施以防止细菌传播和感染”,并已获得麻醉患者安全基金会、Sage Medical Inc.、BBraun、Dräger、Surfaceide 和 Kenall 的资助,有一项或多项专利正在申请中,是 RDB Bioinformatics, LLC(OR PathTrac 母公司)的合作伙伴,曾在 Kenall 和 BBraun 赞助的教育会议上发言。

其他作者均没有利益冲突。

参考文献

- Warner MA, Warner ME. The evolution of the anesthesia patient safety movement in America: lessons learned and considerations to promote further improvement in patient safety. Anesthesiology. 2021;135:963–974. PMID: 34666350

- Dexter F, Loftus RW. Estimation of the contribution to intraoperative pathogen transmission from bacterial contamination of patient nose, patient groin and axilla, anesthesia practitioners’ hands, anesthesia machine, and intravenous lumen. J Clin Anesth. 2024;92:111303. Epub 2023 Oct 22. PMID: 37875062.

- Loftus RW, Brindeiro CT, Loftus CP, et al. Characterizing the molecular epidemiology of anaesthesia work area transmission of Staphylococcus aureus sequence type 5. J Hosp Infect. 2024;143:186–194. Epub 2023 Jul 13. PMID: 37451409.

- Loftus RW, Brown JR, Koff MD, et al. Multiple reservoirs contribute to intraoperative bacterial transmission. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:1236–1248. Epub 2012 Mar 30. PMID: 22467892.

- Hopf, Harriet W. MD. Bacterial reservoirs in the operating room. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2015;120:p 700–702. PMID: 25790198

- Loftus RW, Dexter F, Brown JR. Transmission of Staphylococcus aureus in the anaesthesia work area has greater risk of association with development of surgical site infection when resistant to the prophylactic antibiotic administered for surgery. J Hosp Infect. 2023;134:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2023.01.007. Epub 2023 Jan 21. PMID: 36693592.

- Dexter F, Brown JR, Wall RT, Loftus RW. The efficacy of multifaceted versus single anesthesia work area infection control measures and the importance of surgical site infection follow-up duration. J Clin Anesth. 2023;85:111043. Epub 2022 Dec 23. PMID: 36566648.

- Loftus RW, Dexter F, Goodheart MJ, et al. The effect of improving basic preventive measures in the perioperative arena on Staphylococcus aureus transmission and surgical site infections: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3: e201934. PMID: 32219407

- Wall RT, Datta S, Dexter F, et al. Effectiveness and feasibility of an evidence-based intraoperative infection control program targeting improved basic measures: a post-implementation prospective case-cohort study. J Clin Anesth. 2022; 77:110632. Epub 2021 Dec 17. PMID: 34929497.

- Sharma A, Fernandez PG, Rowlands JP, et al. Perioperative infection transmission: the role of the anesthesia provider in infection control and healthcare-associated infections. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2020;10:233–241. Epub 2020 Jul 17. PMID: 32837343

- Rowlands J, Yeager MP, Beach M, et al. Video observation to map hand contact and bacterial transmission in operating rooms. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:698–701. PMID: 24969122

- WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care: first global patient safety challenge clean care is safer care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. 21, The WHO Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241597906. Accessed July 5, 2024

- Biddle C, Shah J. Quantification of anesthesia providers’ hand hygiene in a busy metropolitan operating room: what would Semmelweis think? Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:756–759. Epub 2012 Feb 9. PMID: 22325482.

- Koff MD, Loftus RW, Burchman CC, et al. Reduction in intraoperative bacterial contamination of peripheral intravenous tubing through the use of a novel device. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:978–985. PMID: 19352154.

- Dexter F, Walker KM, Brindeiro CT, et al. A threshold of 100 or more colony-forming units on the anesthesia machine predicts bacterial pathogen detection: a retrospective laboratory-based analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2024;71:600–610. English. Epub 2024 Feb 27. PMID: 38413516.

- Charnin JE, Hollidge M, Bartz R, et al. A best practice for anesthesia work area infection control measures: what are you waiting for? APSF Newsletter. 2022;37:103-106. https://www.apsf.org/article/a-best-practice-for-anesthesia-

work-area-infection-control-measures-what-are-you-waiting-for/ Accessed August 9, 2024. - WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care: first global patient safety challenge clean care is safer care. Appendix 2. Guide to appropriate hand hygiene in connection with Clostridium difficile spread. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK144042/. Accessed May 29, 2024.

- Pedersen LK, Held E, Johansen JD, Agner T. Short-term effects of alcohol-based disinfectant and detergent on skin irritation. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;52:82–87. PMID: 15725285

- Larson EL, Hughes CA, Pyrek JD, et al. Changes in bacterial flora associated with skin damage on hands of health care personnel. Am J Infect Control. 1998;26:513–521. PMID: 9795681

- Glowicz JB, Landon E, Sickbert-Bennett EE, et al SHEA/IDSA/APIC practice recommendation: strategies to prevent healthcare-associated infections through hand hygiene: 2022 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2023;44:355–376. PMID: 36751708

- Clark C, Taenzer A, Charette K, Whitty M. Decreasing contamination of the anesthesia environment. Am J Infect Control. 2014 Nov;42(11):1223-5. Epub 2014 Oct 30. PMID: 25444268.

- Ali Y, Dolan MJ, Fendler EJ, Larson EL. Alcohols. In: Block SS, ed. Disinfection, sterilization, and preservation. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001:229–254.

- Rutala WA, Weber DJ, and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for disinfection and sterilization in healthcare facilities, 2008. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/47378 Accessed August 9, 2024.

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). NFPA 101 Life Safety Code. 2018 edition. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association; 2018. https://www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/all-codes-and-standards/list-of-codes-

and-standards/detail?code=101 Accessed August 9, 2024. - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Clinical safety: hand hygiene for healthcare workers – fire safety and Alcohol-Based Hand Sanitizer (ABHS). https://www.cdc.gov/clean-hands/hcp/clinical-safety/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/firesafety/index.htm Accessed July 5, 2024.

Issue PDF

Issue PDF